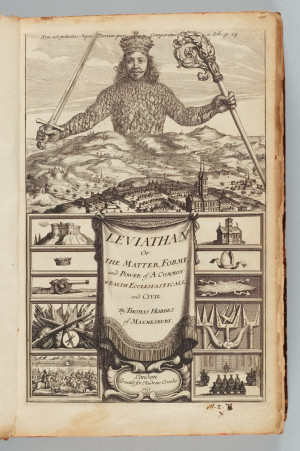

Such an understanding, it is contended, is only very indirectly related to the traditional concerns of the legal philosopher, and hence marginal to a rich and detailed view of law’s nature. Analytical positivism, by contrast, centres upon the possibility of descriptive neutrality: an essential property of law, it is felt, is that ascertainment of its content does not necessarily depend upon moral assessments of the purpose of value of legal rules. Positivism began, therefore, as an explanation of the basis of law’s authority within wider theories of social order: legal rules came to be seen as possessing authority not as the specific outcomes of broader moral precepts, but because they represent definitive, posited solutions to the problems of collective living. For Hobbes, legal positivism represented a decisive break with the intellectual tradition of common law scholarship which could no longer provide a satisfactory account of political authority. Such an understanding of positivism, this essay argues, is both unfruitful and far removed from the concerns of the figure most often associated with the origins of the positivist tradition, Thomas Hobbes. As the sovereign power of a common-wealth is unmatched and gathers all its power from its subjects, Leviathan is an apt symbol for a common-wealth’s strength, as there is nothing on Earth that can be rightly compared to Leviathan.Legal positivism is often described as the view that there is no necessary relationship between law and moral values.

Hee seeth every high thing below him and is King of all the children of pride.” As Hobbes argues that a fear of violence and of God drove humankind to create the common-wealth, it is particularly noteworthy that God made Leviathan not to be afraid. On the original cover of Hobbes’s book, Leviathan is depicted as a giant man whose body is made up of all the individual subjects of the common-wealth.Īccording to Hobbes, God made the “great power of Leviathan,” named him “King of the Proud” and said: “ There is nothing on earth, to be compared with him. Hobbes mentions Leviathan several times in his book and likens the beast to the “Artificial man” that is “the great LEVIATHAN called a COMMON-WEALTH, or STATE.” This analogy is exactly how Hobbes sees the ideal common-wealth: many people united under a single sovereign power, who are stronger together than they could ever be alone. In Thomas Hobbes’s philosophical discourse by the same name, Leviathan is symbolic of the ideal common-wealth. Leviathan, a sea monster from the biblical Book of Job that is usually depicted as giant crocodile, is used within Christianity as a metaphor for the power of people united as one.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)